July 31, 2019 | Day 3, Session 4

Chief Experience Officer at Level Access

We failed when we built this thing that was incredibly accessible. We were contracted by an organization to build them a custom accessible video player. Part of the reason they got that job was because of their experience with accessible video players. They’d done all kinds of research and user testing and had turned that into what they thought was a winning combination of building this accessible video player.

The org that they were building it for had a lot of visually impaired folks that were their target market so this was a perfect opportunity for them to say they needed an incredible accessible video player. Derek and his team said they would be doing it in phases and they were very agile about it. And every 2-3 sprints they’d spot check with actual users.

They did this 2-3 times throughout the project and it was ‘successful’, they created an accessible video player.

One of things they didn’t have was a rewind or fast forward button. Often in a video player, there are a lot of controls and that can make using it difficult. They decided to remove these buttons in response to adding a transcript button. They thought they’d be able to get around the video using the timeline scrubber and wouldn’t need the buttons.

So they put it through its paces, did lots of technical testing and they were getting ready for user testing. Then they get feedback like “I couldn’t find a way to move ahead. I did try the slider, but it didn’t appear to be adjustable.” but they KNEW the timeline scrubber was adjustable!

But what they didn’t take into account is they had this idea that they should test the current version minus 2. Turns out that the person who had this particular issue wasn’t getting any of the announcements that this scrubber was adjustable because they were on a screen reader that was 4 versions old.

That was a little bit of a moment for them where they realized ‘wow we’ve completely missed this,’ and that was not really easy to take. They’re an accessibility agency, it’s all they do, and to get this kind of feedback from a user in testing was hard, it hurt.

So they kept moving forward so they decide they’re going to get other users with different disabilities to test this.

A common thing for someone with low vision we often get a limited view of the screen. This is sometimes because of the physical limitations of their vision or that they have to use a magnifier and so they can only see a small portion of the screen.

They created a simple task of moving the video to the 10-minute mark. This seems innocuous but he demoed that for someone with a limited field of view, and they realized it was a multi-step back and forth process because they couldn’t see the time mark and the scrubber at the same time.

They made it very technically accessible but didn’t consider the impact on people with low vision.

They kept getting feedback like this and they realized they had to go back and redesign and rethink. So they do decide they’ll put in a set of fast forward and rewind buttons.

They did also get feedback that something was up with the screen reader that they didn’t know, and they found that the idea to take the fast forward and rewind buttons away was a bad one. People who had been blind from birth saw the buttons as their primary tool because they’re very used to those buttons on their cassette tapes and VCRs. So buttons are easier for them to understand than a visual slider.

That was great feedback, he just wished he’d had it earlier.

When he said they failed it wasn’t that they created an accessible thing, they did. It was just that they didn’t engage the users early enough to build the right thing. They had built the thing right but they hadn’t built the right thing. The process wasn’t what it should have been.

One of the biggest lessons was that they made some really bad assumptions.

Like that it’s a good idea to remove the buttons. Or that the low vision side of things wasn’t as important as screen readers. Both wrong.

There are 2 kinds of inclusion:

Inclusion in the product

Inclusion in the process

Inclusive design – those words can take on various meanings.

Design can be a noun or a verb.

We can make a thing that is accessible and doesn’t exclude people in lots of different ways. We can make something by accident. We can create a thing that we know is not accessible and then go back and fix it afterward. We can create a thing that is not accessible and create another version of it that’s accessible. We still have accessibility, but it doesn’t mean that we practiced inclusive design in the process.

When we’re talking about inclusion in the process we mean how do we ensure that people with disabilities are involved/included in the design process itself?

The way to do that is by embracing the concept of diversity, by default. Our new normal is that we have no normal. We take that into any design process.

“Nothing about us, without us.” -Michael Masutha

The idea behind that is if you’re creating something for me I should have a reasonably meaningful way of participating in that thing. I should be represented in that somehow.

That’s not just limited to creating digital things, but also things like policy.

In Canada as of June 21 is the accessible Canada act and it’s their effort of making sure the rights and freedoms of people with disabilities are respected. “Nothing without us.”

We don’t want people designing and creating things about us anyway!

We need to reframe the way that we approach design. We’ve heard for many many years that we need to design for people that are not like us because we live in a little bit of a bubble in the tech world.

We’re all nerds.

We hear the phrase a lot ‘we need to design for people not like us. ’He’d like to flip this now, he wants us to design for people like us but redefine what ‘like us’ means.

Let’s redefine what ‘like us’ means.

We could join the largest minority group at any time. 1 in 7 people in the world has a disability. He was born with a club foot – that means that his leg was straight and his foot was out to the side, so he had to have surgery, etc, and this is affecting him now in a way that impacts his day-to-day.

We need to think about who we’re designing for and what we’re designing for. We as an industry can tend to build things to impress other people in the industry, but we shouldn’t be focused on that most of the time. (paraphrasing)

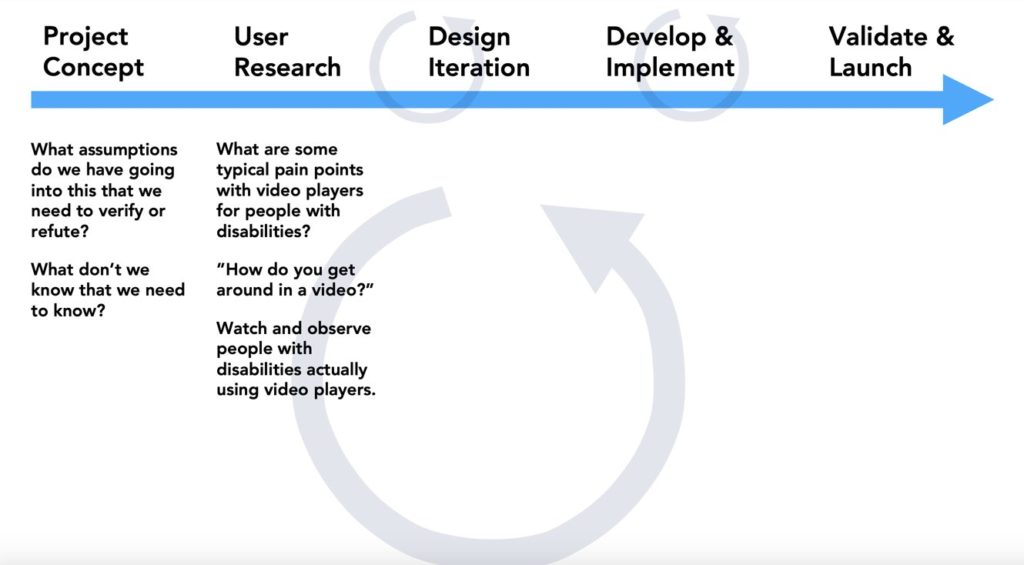

What we’re doing right now often is testing with people who have disabilities. This is very typical and in most cases, if you’re doing usability testing right now at the end of an iteration or right before a launch you’re already ahead of most of your competition because most people aren’t doing this at all.

But when we do this we’re saying ‘hey we built a thing and we want you to tell us now whether we did it right or not.’

Shift Left.

Can we do this earlier in the process? Find a way to make it earlier. Incorporate people with disabilities early.

When we take people with disabilities and incorporate them into the process earlier, we’re saying ‘we want your ideas, and you have something valuable and important to contribute as well.’ This is when we start making a difference in inclusive design.

When we do this, the way that it is here, we hold all the power in the relationship. We’re the ones that are designing and the people we’re designing for only have the say to tell us what they think about it. That’s a power dynamic he hadn’t thought about before.

The greatest power we have as designers is to give that power away.

The action he’s hoping we take from this is that we go out there and acknowledge our privilege, our power, and our position in the design process.

We choose when people get to contribute, no other time.

One of the best questions that we could ask is ‘how might you like to contribute to this project?’ That’s different than saying ‘we’ll call you in 8 weeks.’

Inclusion is taking on many different meanings and when you look at companies’ statements about inclusion and equalities, people with disabilities are being forgotten again.

What can we do to move this inclusion earlier in the process?

What assumptions are going into this that we need to verify or refute? What don’t we know that we need to know? Then do the research!

Ask “What problems are people trying to solve? What are the opportunities?”

The Big Life Fix BBC Series

* a show to check out

People hack on things. We create things we need all the time as part of innovation. Some of these hacks are incredible.

So, it makes total sense to ask “How are people with disabilities already solving this problem?”

Because there is probably already a hack and that can help inform your design!

When Microsoft was going through the design of the Xbox adaptive controller (a device designed specifically for people with motion and dexterity-related disabilities), they asked what people have always done for this and how does this informs what we’re about to build.

So they looked at how people had been hacking gaming handsets and they used that information to design their product!

microsoft.com/design/inclusive

Bryce was on the team that helped design that Xbox adaptive controller. He said the #1 thing he tells people is “don’t think of people that are specifically using this controller when designing and building, just let go of the assumption that people are holding onto a controller with both hands. He wants people to let go of how they’re framing the problem.”

Dereks’ favorite part of the XAC is the packaging. It’s just as much a story of inclusive design as everything else. They used GRAVITY as one of their design materials!!! It just FALLS OPEN as things are pulled.

They actually said, “we want to design a teeth-free packaging experience.” Well ALL OF US USE OUR DAMN TEETH TO OPEN PACKAGING so this benefits ERRRRBODY.

Another great example of an adaptation that helps everybody is the ‘blur and darken background option in Skype came from a developer who is deaf and had to keep asking her parents to close the curtains or turn off the lights so she can read their lips better.

Another example is the “I can fly” program for people with autism to help improve the flying experience. They created a checklist for each section of the flying experience with simple instructions and icons they’re familiar with. This really sets an expectation about what is this experience to be like so it’s easier for a person with autism to react to it. His favorite part is the explicit ‘all done with a smiley face at the end of each checklist. He loves it because it’s an explicit thing that signifies accomplishment.

Lessons

- We need to start earlier

- We know less than we think

- Other people know more than we think.

How do we go about doing this?

Dexterity is fine motor control and fine motor movements (ex: someone with a tremor)

Mobility is stuff like using a scooter or a wheelchair or crutches.

We have to be intentional about inclusion. Not excluding people intentionally is not enough and is not a good excuse.

Let’s think about the tools and processes we use in design and do those allow people with disabilities to participate?

Can you help meet these inclusivity goals?

Participation: You should have the ability and opportunity to participate in solutions that you will use, and that will impact your life.

Value: Your participation in a process is valued rather than tolerated or accommodated.

Belonging / Othering: Your participation should be predicated on using the same tools, at the same time, in the same space, using the same process as anyone, to the greatest extent possible.

Same space, same place, same process.

We don’t want people to feel like they’re being ‘othered.’

How do we measure inclusion?

This is one of the most important questions we can ask because it will allow us to show that we’re getting better at this over time.

@feather

0 Comments